What do we know about the “alarming” rise in measles cases in Europe?

Data focuses on just two specific years, failing to acknowledge the long-term evolution of the illness

What has been said?

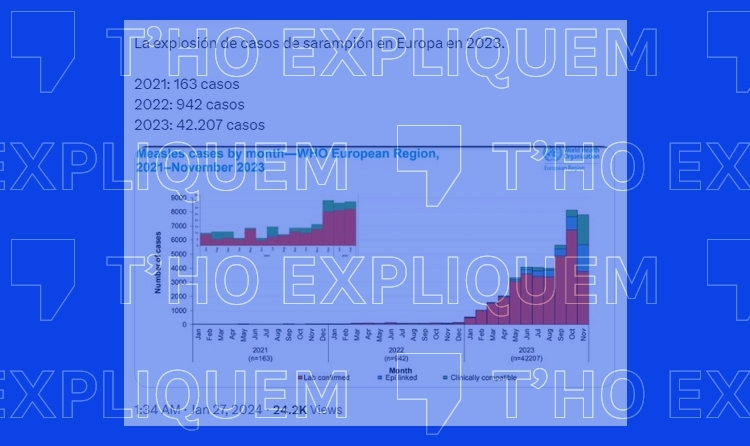

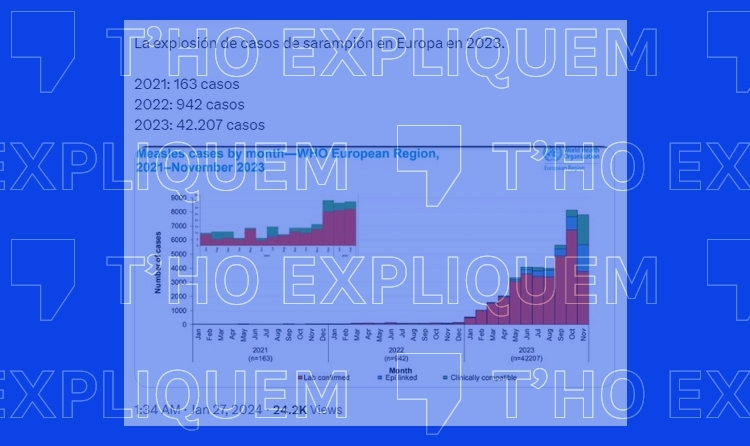

Measles cases went up 45-fold in 2023 in Europe with relation to the previous year.

What do we know?

While the data are true, they focus on just two specific years, failing to acknowledge the long-term evolution of the illness as well as the situation before the covid-19 pandemic and the effect of the restrictions put into place starting in 2020. In fact, before the pandemic, in 2018 and 2019, the case numbers were higher – approximately twice as high – than those in experienced on the European continent in 2023.

There is a lot of talk on social media about the rise in measles cases in Europe between 2022 and 2023, which jumped from 940 to over 40,000 in just eleven months. Several media outlets, the World Health Organization (WHO) and individual accounts have focused on the 45-fold increase in infections in one year, with some profiles talking about an “explosive” increase, and the WHO calling it “alarming”.

While the data are true, they focus on just two specific years, failing to acknowledge the long-term evolution of the illness as well as the situation before the covid-19 pandemic and the effect of the restrictions put into place starting in 2020. In fact, before the pandemic, in 2018 and 2019, the case numbers were higher – approximately twice as high – than those in experienced on the European continent in 2023. Ignoring the fact that the number of cases is not so different from before the pandemic – or is even lower – may lead people to interpret the situation as being a lot more serious or abnormal than it really is. Let us explain!

The number of measles cases in Europe grew rapidly in 2018 and 2019 before taking a sharp turn downward in 2020. This change can be explained, to a great extent, by the individual and collective safety measures taken between 2020 and 2022 during the covid-19 pandemic. Lockdowns, social distancing and mask usage had “an impact on slowing the spread of measles cases”, pediatrician, epidemiologist and director of the Institute of Global Health in Barcelona (ISGlobal) Quique Bassat explained to Verificat.

That is why this spike in cases of measles – a highly contagious viral infection that killed over two million people a year before vaccines were developed in the 1960s – “was more or less to be expected” once restraints on social activities were lifted and life went back to normal, the expert pointed out. This spike was also observed in other viral illnesses, such as the flu.

Data out of context

Many articles in the media are saying that measles cases went up 45-fold with relation to the previous year, but they ignore the fact that the increase is with respect to a very low and unusual number. The 900 cases recorded on the European continent in 2022 were the second-lowest annual number since 2006, the first year data was collected. Before the pandemic, the lowest number of annual cases, in 2016, was 7 times higher than the number in 2022; and the average number of cases between 2006 and 2017 – before the increase in 2018 – was 26 times higher.

The current situation is comparable to the one that existed before the pandemic. Looking at the numbers in absolute terms, we can see that around 40,000 cases were recorded in the first 11 months of 2023, but that there were over 100,000 infections in 2019.

What is behind the rise in cases?

The rise in measles cases that Europe has been experiencing since 2018 has to do above all with the non-vaccinated population, as reported by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Vaccine coverage has been falling in certain countries on the European continent for years, such as Romania and Kazakhstan, where many of the cases are occurring, leaving thousands of children vulnerable to infection.

Before the pandemic, the WHO had made various calls to increase vaccine coverage, which is consistent with the recent analyses of the ECDC. Even in countries with high vaccine rates, such as Spain, there are groups of the population that, whether due to vaccine refusal or difficulty in accessing vaccines, continue to have lower vaccination rates. “It is key to identify and reach individuals who are eligible for vaccination, with the goal of getting them vaccinated in line with their national vaccine schedule”, the ECDC concluded.

“Global paranoia”

The director of ISGlobal attributes the media coverage and the alarmist tone generated by this spike in cases to “a global paranoia when talking about any sort of infectious disease outbreak”, motivated by “the fear that we’ve been carrying with us since the pandemic”.

The expert believes that we do need to be talking about these outbreaks (which in the past would occur without people taking much notice), “because it is giving us an argument […] to improve vaccine coverage”, but he recommends doing so without scaremongering.